Render, Commit, and Mount

This document refers to the architecture of the new renderer, Fabric, that is in active roll-out.

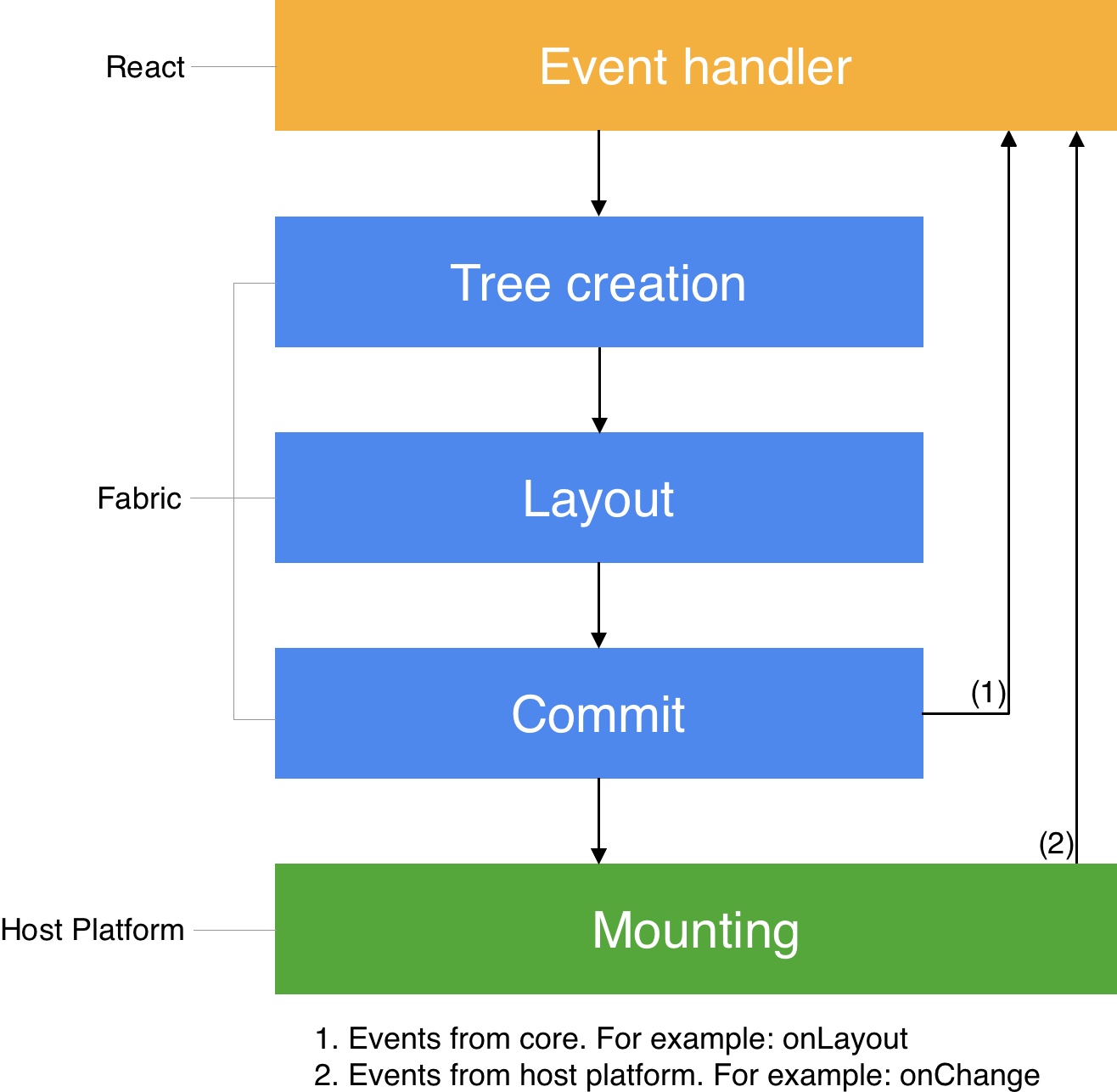

The React Native renderer goes through a sequence of work to render React logic to a host platform. This sequence of work is called the render pipeline and occurs for initial renders and updates to the UI state. This document goes over the render pipeline and how it differs in those scenarios.

The render pipeline can be broken into three general phases:

- Render: React executes product logic which creates a React Element Trees in JavaScript. From this tree, the renderer creates a React Shadow Tree in C++.

- Commit: After a React Shadow Tree is fully created, the renderer triggers a commit. This promotes both the React Element Tree and the newly created React Shadow Tree as the “next tree” to be mounted. This also schedules calculation of its layout information.

- Mount: The React Shadow Tree, now with the results of layout calculation, is transformed into a Host View Tree.

The phases of the render pipeline may occur on different threads. Refer to the Threading Model doc for more detail.

The render pipeline is executed in three different scenarios:

Initial Render

Imagine you want to render the following:

function MyComponent() {

return (

<View>

<Text>Hello, World</Text>

</View>

);

}

// <MyComponent />

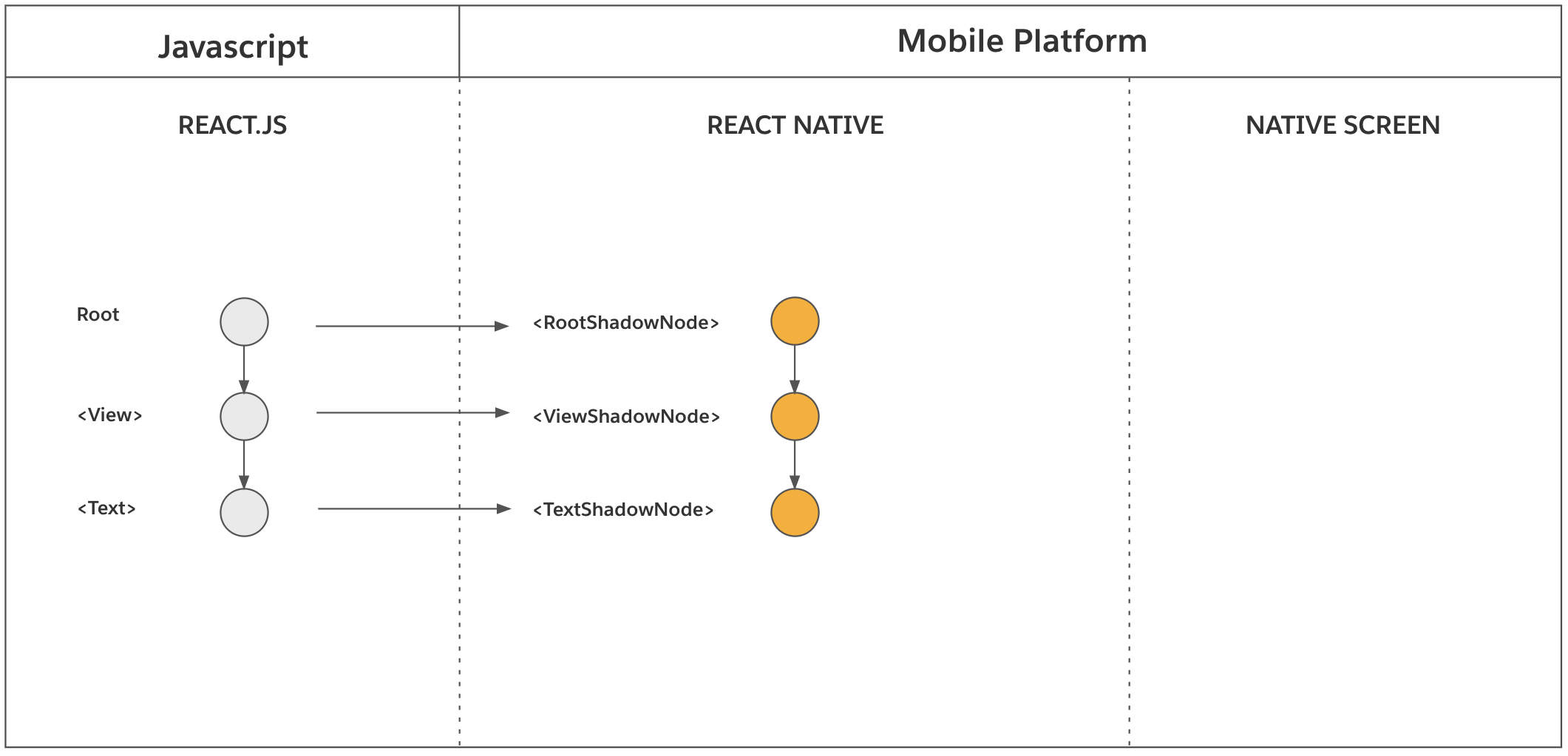

In the example above, <MyComponent /> is a React Element. React recursively reduces this React Element to a terminal React Host Component by invoking it (or its render method if implemented with a JavaScript class) until every React Element cannot be reduced any further. Now you have a React Element Tree of React Host Components.

During this process of element reduction, as each React Element is invoked, the renderer also synchronously creates a React Shadow Node. This happens only for React Host Components, not for React Composite Components. In the example above, the <View> leads to the creation of a ViewShadowNode object, and the

<Text> leads to the creation of a TextShadowNode object. Notably, there is never a React Shadow Node that directly represents <MyComponent>.

Whenever React creates a parent-child relationship between two React Element Nodes, the renderer creates the same relationship between the corresponding React Shadow Nodes. This is how the React Shadow Tree is assembled.

Additional Details

- The operations (creation of React Shadow Node, creation of parent-child relationship between two React Shadow Nodes) are synchronous and thread-safe operations that are executed from React (JavaScript) into the renderer (C++), usually on the JavaScript thread.

- The React Element Tree (and its constituent React Element Nodes) do not exist indefinitely. It is a temporal representation materialized by “fibers” in React. Each “fiber” that represents a host component stores a C++ pointer to the React Shadow Node, made possible by JSI. Learn more about “fibers” in this document.

- The React Shadow Tree is immutable. In order to update any React Shadow Node, the renderer creates a new React Shadow Tree. However, the renderer provides cloning operations to make state updates more performant (see React State Updates for more details).

In the example above, the result of the render phase looks like this:

After the React Shadow Tree is complete, the renderer triggers a commit of the React Element Tree.

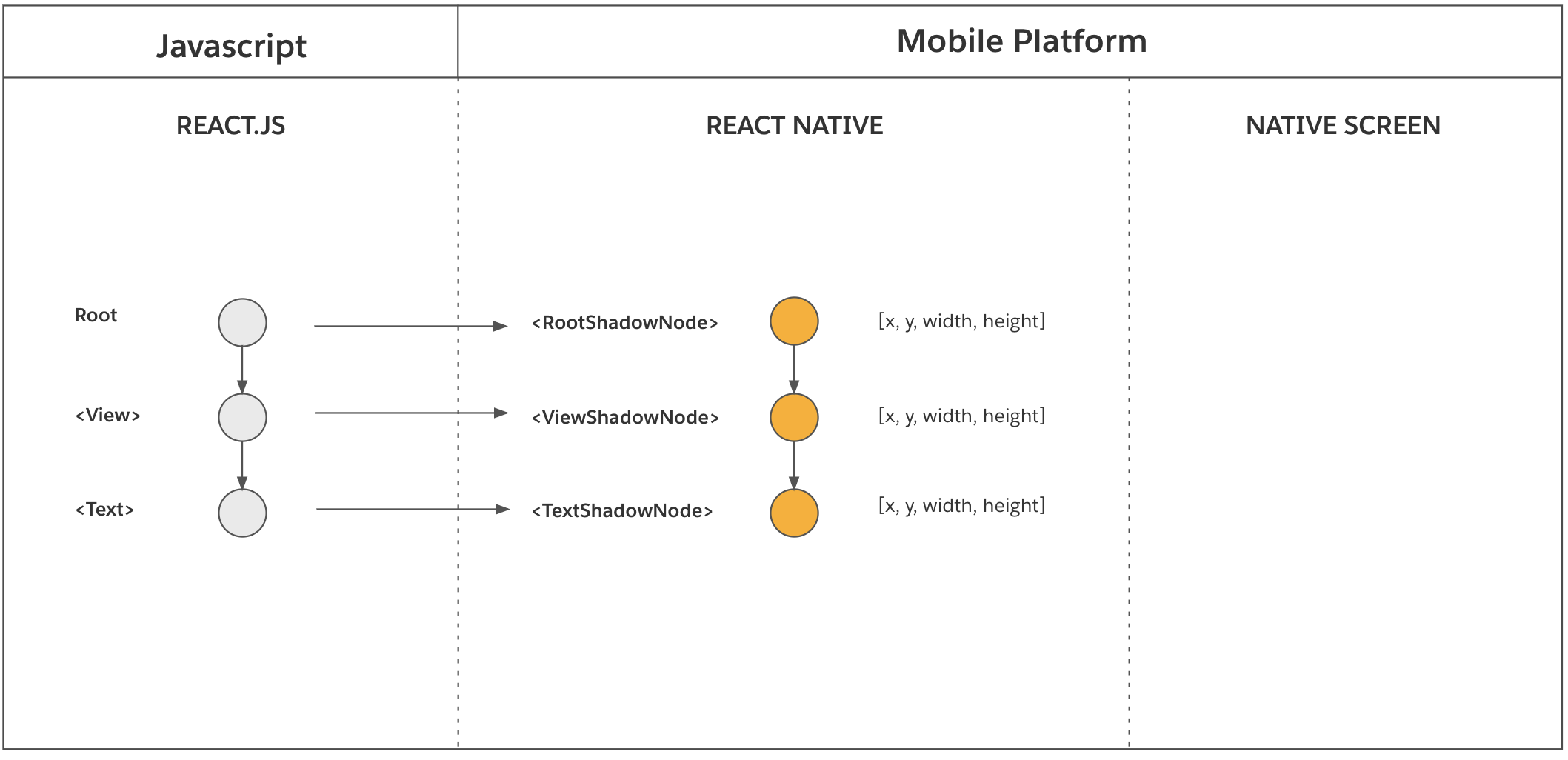

The commit phase consists of two operations: Layout Calculation and Tree Promotion.

- Layout Calculation: This operation calculates the position and size of each React Shadow Node. In React Native, this involves invoking Yoga to calculate the layout of each React Shadow Node. The actual calculation requires each React Shadow Node’s styles which originate from a React Element in JavaScript. It also requires the layout constraints of the root of the React Shadow Tree, which determines the amount of available space that the resulting nodes can occupy.

- Tree Promotion (New Tree → Next Tree): This operation promotes the new React Shadow Tree as the “next tree” to be mounted. This promotion indicates that the new React Shadow Tree has all the information to be mounted and represents the latest state of the React Element Tree. The “next tree” mounts on the next “tick” of the UI Thread.

Additional Details

- These operations are asynchronously executed on a background thread.

- Majority of layout calculation executes entirely within C++. However, the layout calculation of some components depend on the host platform (e.g.

Text,TextInput, etc.). Size and position of text is specific to each host platform and needs to be calculated on the host platform layer. For this purpose, Yoga invokes a function defined in the host platform to calculate the component’s layout.

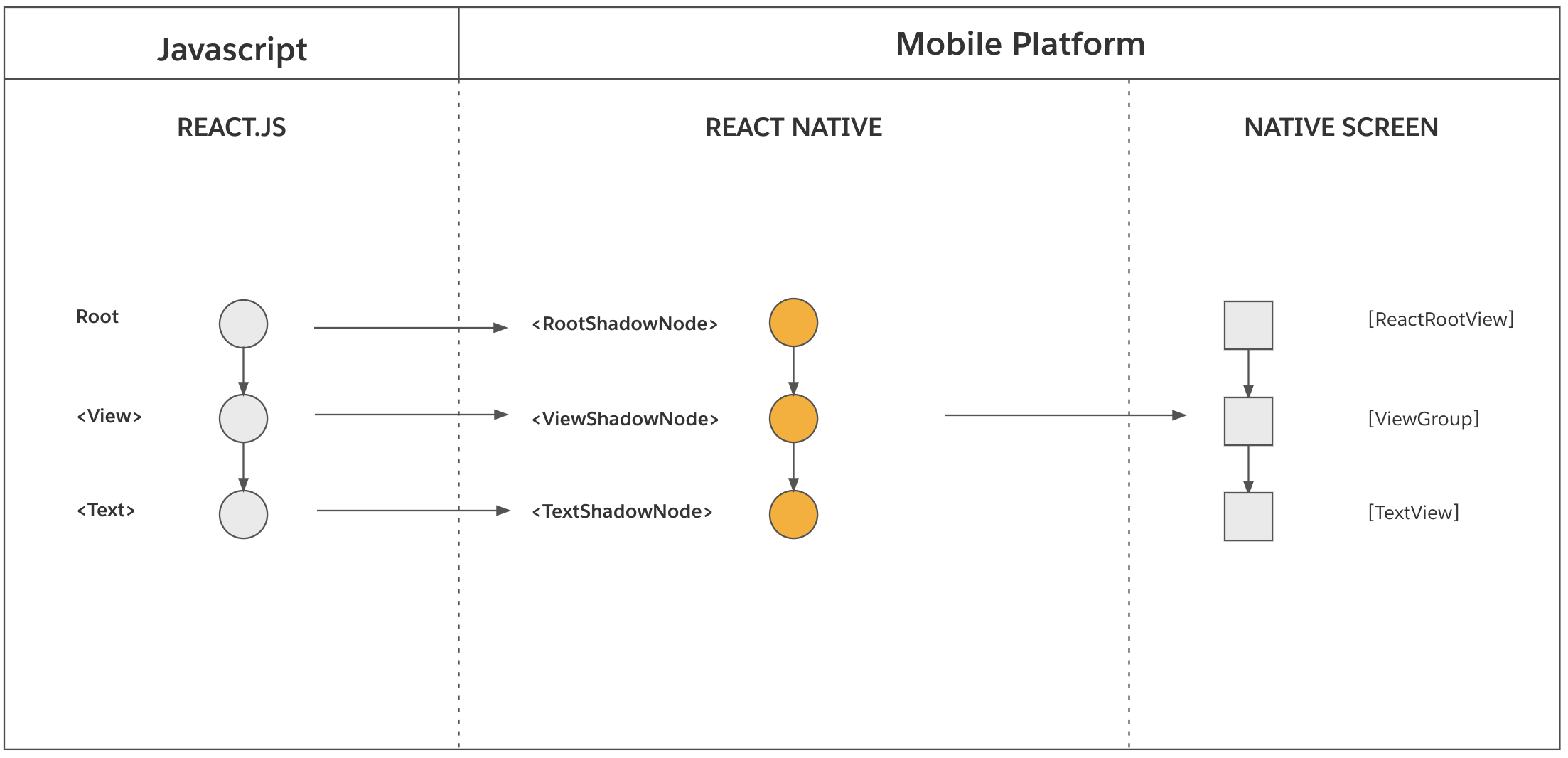

The mount phase transforms the React Shadow Tree (which now contains data from layout calculation) into a Host View Tree with rendered pixels on the screen. As a reminder, the React Element Tree looks like this:

<View>

<Text>Hello, World</Text>

</View>

At a high level, React Native renderer creates a corresponding Host View for each React Shadow Node and mounts it on screen. In the example above, the renderer creates an instance of android.view.ViewGroup for the <View> and android.widget.TextView for <Text> and populates it with “Hello World”. Similarly for iOS a UIView is created with and text is populated with a call to NSLayoutManager. Each host view is then configured to use props from its React Shadow Node, and its size and position is configured using the calculated layout information.

In more detail, the mounting phase consists of these three steps:

- Tree Diffing: This step computes the diff between the “previously rendered tree” and the “next tree” entirely in C++. The result is a list of atomic mutation operations to be performed on host views (e.g.

createView,updateView,removeView,deleteView, etc). This step is also where the React Shadow Tree is flattened to avoid creating unnecessary host views. See View Flattening for details about this algorithm. - Tree Promotion (Next Tree → Rendered Tree): This step atomically promotes the “next tree” to “previously rendered tree” so that the next mount phase computes a diff against the proper tree.

- View Mounting: This step applies the atomic mutation operations onto corresponding host views. This step executes in the host platform on UI thread.

Additional Details

- The operations are synchronously executed on UI thread. If the commit phase executes on background thread, the mounting phase is scheduled for the next “tick” of UI thread. On the other hand, if the commit phase executes on UI thread, mounting phase executes synchronously on the same thread.

- Scheduling, implementation, and execution of the mounting phase heavily depends on the host platform. For example, the renderer architecture of the mounting layer currently differs between Android and iOS.

- During the initial render, the “previously rendered tree” is empty. As such, the tree diffing step will result in a list of mutation operations that consists only of creating views, setting props, and adding views to each other. Tree diffing becomes more important for performance when processing React State Updates.

- In current production tests, a React Shadow Tree typically consists of about 600-1000 React Shadow Nodes (before view flattening), the trees get reduced to ~200 nodes after view flattening. On iPad or desktop apps, this quantity may increase 10-fold.

React State Updates

Let’s explore each phase of the render pipeline when the state of a React Element Tree is updated. Let’s say, you’ve rendered the following component in an initial render:

function MyComponent() {

return (

<View>

<View

style={{ backgroundColor: 'red', height: 20, width: 20 }}

/>

<View

style={{ backgroundColor: 'blue', height: 20, width: 20 }}

/>

</View>

);

}

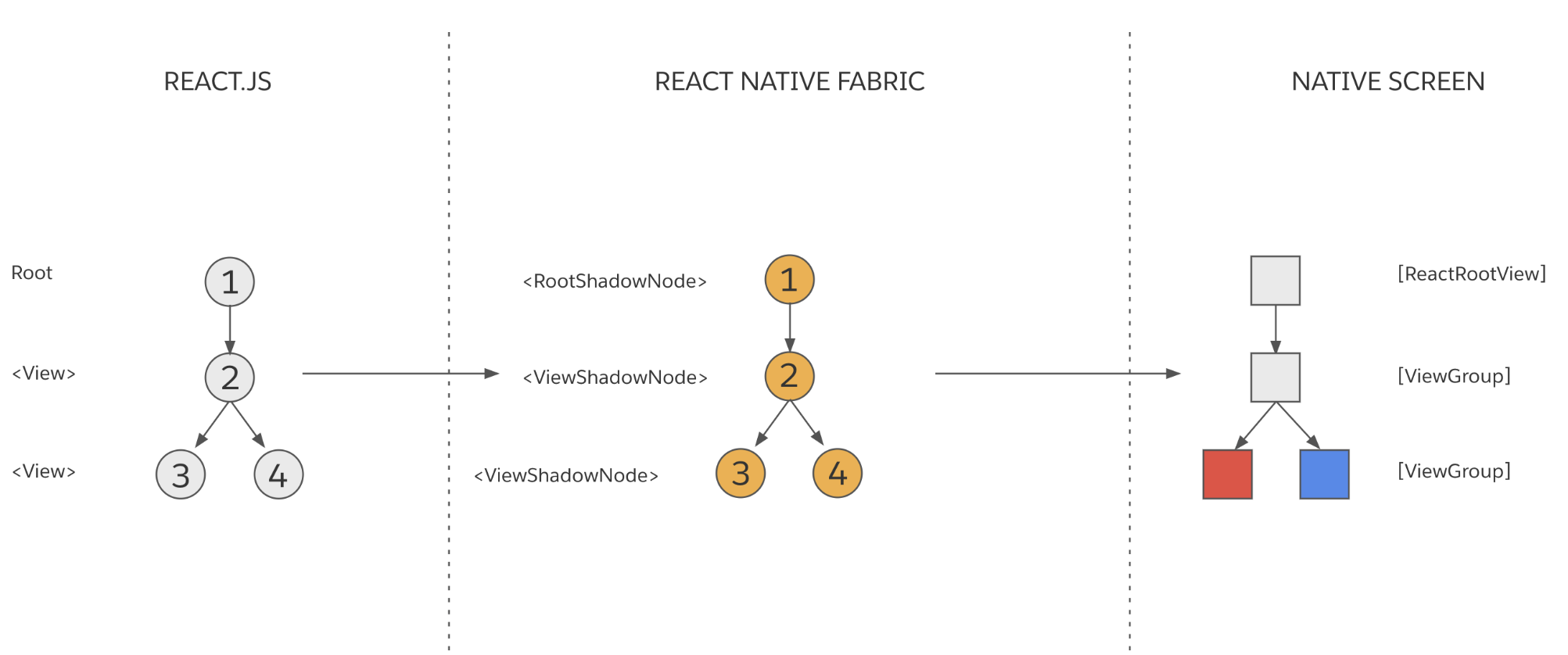

Applying what was described in the Initial Render section, you would expect the following trees to be created:

Notice that Node 3 maps to a host view with a red background, and Node 4 maps to a host view with a blue background. Assume that as the result of a state update in JavaScript product logic, the background of the first nested <View> changes from 'red' to 'yellow'. This is what the new React Element Tree might look:

<View>

<View

style={{ backgroundColor: 'yellow', height: 20, width: 20 }}

/>

<View

style={{ backgroundColor: 'blue', height: 20, width: 20 }}

/>

</View>

How is this update processed by React Native?

When a state update occurs, the renderer needs to conceptually update the React Element Tree in order to update the host views that are already mounted. But in order to preserve thread safety, both the React Element Tree as well as the React Shadow Tree must be immutable. This means that instead of mutating the current React Element Tree and React Shadow Tree, React must create a new copy of each tree which incorporates the new props, styles, and children.

Let’s explore each phase of the render pipeline during a state update.

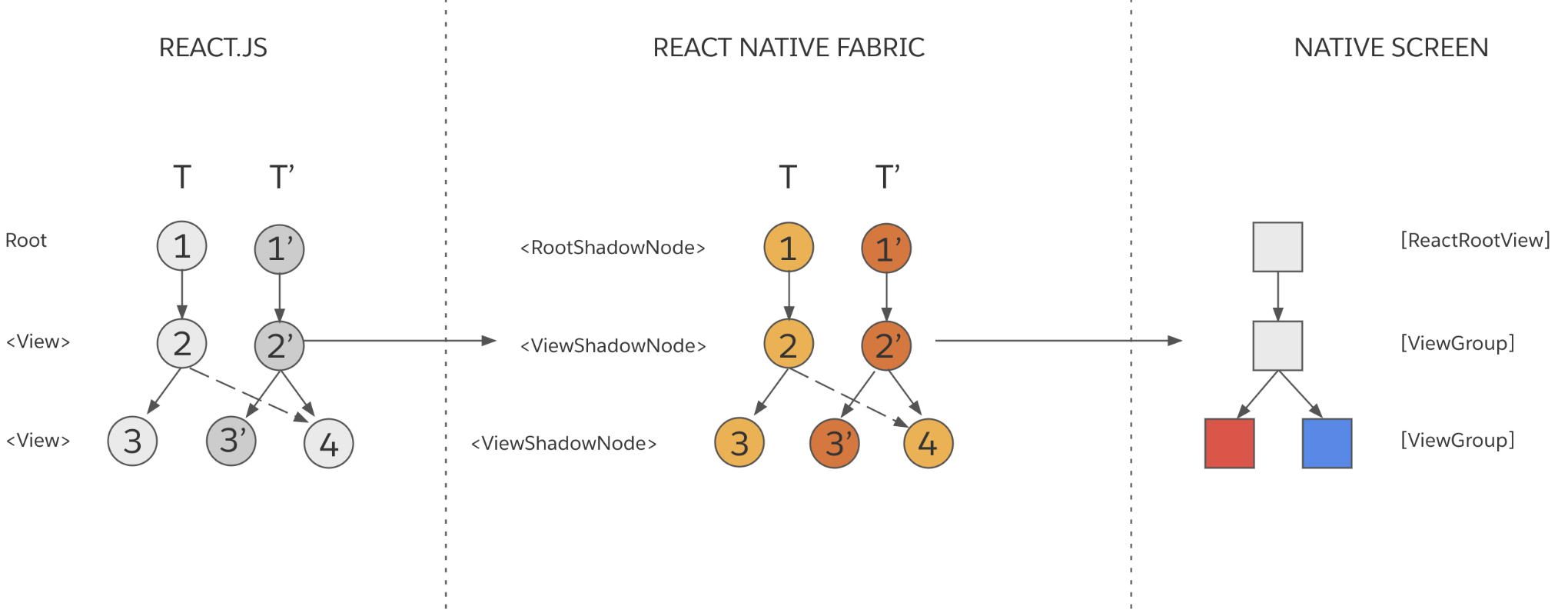

When React creates a new React Element Tree that incorporates the new state, it must clone every React Element and React Shadow Node that is impacted by the change. After cloning, the new React Shadow Tree is committed.

React Native renderer leverages structural sharing to minimize the overhead of immutability. When a React Element is cloned to include the new state, every React Element that is on the path up to the root is cloned. React will only clone a React Element if it requires an update to its props, style, or children. Any React Elements that are unchanged by the state update are shared by the old and new trees.

In the above example, React creates the new tree using these operations:

- CloneNode(Node 3, {backgroundColor: 'yellow'}) → Node 3'

- CloneNode(Node 2) → Node 2'

- AppendChild(Node 2', Node 3')

- AppendChild(Node 2', Node 4)

- CloneNode(Node 1) → Node 1'

- AppendChild(Node 1', Node 2')

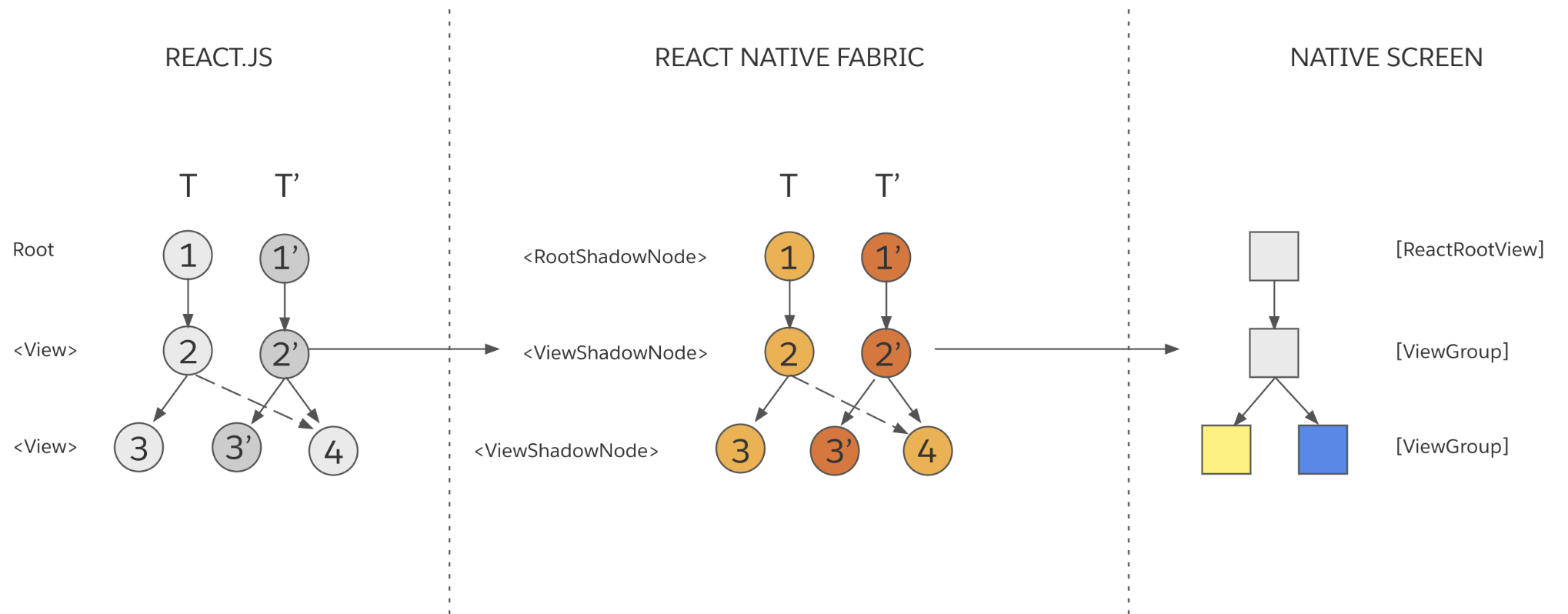

After these operations, Node 1' represents the root of the new React Element Tree. Let's assign T to the “previously rendered tree” and T' to the “new tree”:

Notice how T and T' both share Node 4. Structural sharing improves performance and reduces memory usage.

After React creates the new React Element Tree and React Shadow Tree, it must commit them.

Layout Calculation: Similar to Layout Calculation during Initial Render. One important difference is that layout calculation may cause shared React Shadow Nodes to be cloned. This can happen because if the parent of a shared React Shadow Node incurs a layout change, the layout of the shared React Shadow Node may also change.

Tree Promotion (New Tree → Next Tree): Similar to Tree Promotion during Initial Render.

Tree Diffing: This step computes the diff between the “previously rendered tree” (T) and the “next tree” (T'). The result is a list of atomic mutation operations to be performed on host views.

- In the above example, the operations consist of:

UpdateView(**Node 3'**, {backgroundColor: '“yellow“})

- In the above example, the operations consist of:

- Tree Promotion (Next Tree → Rendered Tree): This step atomically promotes the “next tree” to “previously rendered tree” so that the next mount phase computes a diff against the proper tree. Diff can be calculated for any currently mounted tree with any new tree. The renderer can skip some intermediate versions of the tree.

- View Mounting: This step applies the atomic mutation operations onto corresponding host views. In the above example, only the

backgroundColorof View 3 will be updated (to yellow).

React Native Renderer State Updates

For most information in the Shadow Tree, React is the single owner and single source of truth. All data originates from React and there is a single-direction flow of data.

However, there is one exception and important mechanism: components in C++ can contain state that is not directly exposed to JavaScript, and JavaScript is not the source of truth. C++ and Host Platform control this C++ State. Generally, this is only relevant if you are developing a complicated Host Component that needs C++ State. The vast majority of Host Components do not need this functionality.

For example, ScrollView uses this mechanism to let the renderer know what’s the current offset. The update is triggered from the host platform, specifically from the host view that represents the ScrollView component. The information about offset is used in an API like measure. Since this update stems from the host platform, and does not affect the React Element Tree, this state data is held by C++ State.

Conceptually, C++ State updates are similar to the React State Updates described above. With two important differences:

- They skip the “render phase” since React is not involved.

- The updates can originate and happen on any thread, including the main thread.

When performing a C++ State update, a block of code requests an update of a ShadowNode (N) to set C++ State to value S. React Native renderer will repeatedly attempt to get the latest committed version of N, clone it with a new state S, and commit N’ to the tree. If React, or another C++ State update, has performed another commit during this time, the C++ State commit will fail and the renderer will retry the C++ State update many times until a commit succeeds. This prevents source-of-truth collisions and races.

The Mount Phase is practically identical to the Mount Phase of React State Updates. The renderer still needs to recompute layout perform a tree diff, etc. See above sections for details.